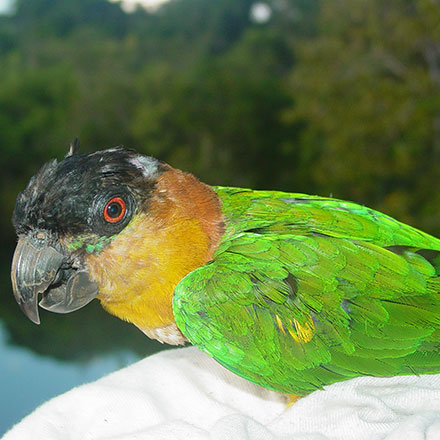

© J.D. Weckstein

White-flanked Antwren

Myrmotherula axillaris

Mixed-species flocks often specialize on certain resources in specific areas of the forest. For example, understory flocks typically feed on insects and other invertebrates, whereas canopy flocks can be made up of either fruit- or insect-eating bird species.

Mated pairs of White-flanked Antwrens seemed to be common members of insect-eating mixed flocks at all of our study sites.

White-flanked Antwren Song