Changing Conservation Priorities

Environments that are home to the greatest number of rare plants and animals generally command the highest conservation rankings. However, the assessment of a region's diversity is shaped by what kinds of organisms researchers look for and where they look. As a result, the areas typically targeted as top priority for protection are places where scientists have collected the most data—often high-profile locations harboring specific species.

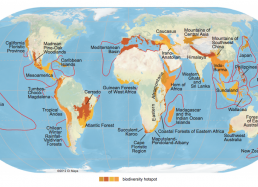

But what about inhospitable or remote regions of the world where few explorations have occurred? And how about species that are hard to find or perceived as less appealing? Do they warrant a lower priority simply because they're not as well-known? What we're learning about bryophytes is revealing a bias in how we study plants and animals and define "biodiversity hotspots."

Size and Spectacle Matter

In the scientific world, the larger, showier species are often the most well-studied. For example, in the last 20 years, more than 80% of the publications on animal conservation have been devoted to vertebrates (animals with backbones), despite the fact that this group makes up less than 5% of the known animal species. And among vertebrates, birds and mammals are the focus in 70% of scientific articles, although fishes, amphibians, and reptiles comprise 70% of the known animals with backbones.

The same is true for plants: most botanical publications feature species that flower and have vascular (circulatory) systems—even though this group is a minority in many parts of the world. Recent Field Museum studies of liverworts, mosses, and other non-flowering plants are helping to train the scientific lens on species that were once "invisible," bringing balance to the conservation equation.

Familiarity Breeds Fondness

Currently, about 30% of publications with a conservation focus concentrate on the northern hemishere, specifically the forests of North America and Europe. While this may be due to the fact that species living in more inhabited areas of the world may face greater threats and inspire greater public sympathy because of their familiarity, there is a "downside." The belief has arisen that the areas furthest from the equator harbor fewer species and are therefore of lesser concern.

Research by Field Museum scientists and their collaborators has revealed that the diversity of smaller life forms, such as lichens, bryophytes, insects, and other invertebrates, actually increases towards Earth's poles, where few large species endure. And spreading the word about the beauty and ecological value of organisms living in these miniature forests is helping to spur public interest, caring, and conservation action in regions of the world once largely ignored.