4: "Sok kicsi sokra megy!" (Many small things can add up to quite a lot!)

This Hungarian saying must have been written by an archaeologist! Archaeological science is all about making little things—pottery fragments, chunks of daub, pieces of stone tools—add up to one big, coherent picture of what happened in the past. As a result of all our hard work over the last two years, those small pieces are finally coming together, and we’re beginning to get an understanding of how the site at Szeghalom-Kovácshalom became a major regional center at the end of the Neolithic period.

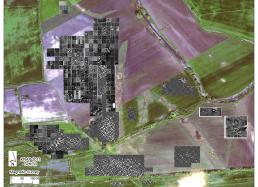

In short, our work this year both confirmed and challenged our findings from last year. As we suspected in 2010, Szeghalom-Kovácshalom is indeed made up of three distinct and separate zones of use—the tell, the horizontal settlements, and the longhouses. But in 2011, we learned that the dividing lines between these zones are blurry, with one blending into the next.

Surprisingly, almost all of the dateable material collected at the site seems to come from the Late Neolithic period, meaning that this tell-settlement-longhouse community formed fairly rapidly and lasted for a relatively brief period of time (see above photo.) Future seasons will help us pinpoint a more precise timeframe for the site’s development and help us uncover factors that may have contributed to the community’s rapid rise and decline. To learn more about our conclusions, take a look at my summary of the season’s findings, “2011: Digging Begins,” and be sure to check out the new “2011 Season Photo Gallery” that I’ve added to the Expeditions’ website.

But I’m getting ahead of myself…. When last I wrote, we were in the throes of finishing up the final week of our Spring 2011 field season in Hungary. We managed to find a good breaking point in our fieldwork and say goodbye to the site in time to pack up all the equipment and the finds. Most importantly, we had enough time to back up all of our electronic information and distribute backup copies of the datasets across the world. (After doing all this work, we’d hate to lose all this invaluable information.)

One copy of our datasets went to Crete, Greece, one copy went to Szeged, Hungary, and another couple of copies came back to the U.S. and are now in Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Columbus. This obsession with documentation is not just about me being overly paranoid! That might be part of it, but in the end, all archaeologists need to be obsessed with documenting their work because the process of archaeological fieldwork is, ultimately, destructive (see Photo #1 below.)

This causes a scientific conundrum for us. Almost all the models we build of the past are based upon the physical and spatial relationships between things—the location of an artifact within a stratigraphic sequence tells us about chronology; the spatial relationship between a stone arrowhead and a skeleton tells us about human behavior. These physical and spatial relationships are what archaeologists call ‘contextual information,’ and without that ‘context,’ it’s difficult to say anything meaningful about what happened in the past. An artifact with no contextual information is significantly less useful than one with good context.

So, here is the conundrum. It’s kind of like an archaeological ‘Heisenberg Principle’—the principle in quantum physics that states that the act of observation affects the actual result of an experiment. The process of recovering information in archaeology—whether it's during excavation or during surface collection—ultimately destroys context. Once we've ‘measured’ the quantity of a cluster of artifacts in a surface collection unit (by picking them up) or the depth of a pit in an excavation trench (by digging it out), we cannot go back and reconstruct those features. Their context is destroyed.

That’s why it is so important for archaeologists to meticulously record everything they encounter, even if it might seem inconsequential at the time. We've got only one shot, and we need to get it right the first time. This is why we go out of our way to use non-destructive techniques like magnetometry, or minimally-destructive techniques like soil chemistry, to learn as much as we can before we start in with more destructive methods that destroy context (see Photo #2 below.)

And speaking of samples, as I write, Attila is walking our various samples through the export process in Hungary. We’re fortunate that the Hungarian government still permits us to export samples for specific analyses. The soil samples from the cores will be split—half of each sample goes to Crete and is analyzed for magnetic susceptibility, the other half is shipped to the U.S. and will be subject to elemental analyses.

Fragments of ceramics and clay samples will be shipped back to The Field Museum and will be analyzed using our mass spectrometer to determine whether the ceramics were made on-site, or whether they were brought into the site through trade. Samples of bones, charcoal, and plant remains will be sent out for radiocarbon analyses, and will provide us with absolute dates that we can use to estimate how long different parts of the site were used over time (see Photo #3 below.) It will be critical to have this information before we go back into the field next year.

We can fund two more years of research through our continuing federal grants, and we still have a lot to do! In addition to hammering away at the geophysical survey and the intensive surface collections at Szeghalom-Kovácshalom, we want to continue to work at the other tell nearby—Vészto-Mágor. We also need to open up much larger excavation units to expose more features, such as the big longhouse to the north of the tell, which we discovered this year during our magnetometry survey. We also need to identify the old excavation trenches at the tells and clean back the profiles to take samples that we can compare to those we’ve collected from other parts of the sites.

At the regional scale, we’ll continue to use satellite imagery and imagery collected by aerial flyovers in airplanes to compare the signatures we’re collecting at Szeghalom-Kovácshalom with other anomalies throughout the region. This will permit us to identify similar features at other sites in the region. We’ll also continue to work with our Hungarian colleagues to sink cores into the ancient riverbeds and wetlands around the site to reconstruct how the environment has changed over the last 10,000 years.

We look forward to sharing the results of our analyses with you in the months to come, and hope that you’ll continue to join us when we head back into the field next spring!

Best,Bill