The Mitla Fortress

The Field Museum first conducted studies in the Valley of Oaxaca more than 100 years ago, when former Curator William H. Holmes explored the region and observed that many of the surrounding hills were shaped by remnants of ancient settlements. Today, we know that more than 100 hilltop centers, each with flattened terraces used for housing (not farming), are situated on the region’s mountain crests and slopes.

The Mitla Fortress itself is perched on a steep, rocky hill that rises starkly from the floor of the eastern branch (the Tlacolula "arm") of the Valley of Oaxaca. Famous archaeological explorer Guillermo Dupaix was the first to publish accounts of the fortress in the early 1800s. His records included plans of stone walls that encircle the top of the fortress and indicate that at some point during the site’s life, its people felt the need for greater protection.

Placing the Fortress in Context

The Mitla Fortress can be considered part of the larger and more famous Zapotec settlement of Mitla, which lies under the present-day town of the same name located several kilometers to the west. An outlying "suburb" of this larger city, the fortress was likely only fortified late in its history, long after the fall of Monte Albán. Pottery sherds found on the surface of most of its more than 400 recorded terraces tell of the site's longevity and date from the height of the Zapotec state (Classic period, A.D. 200-850) through the arrival of the Spanish at the end of the Postclassic period, A.D. 850-1520.

Although Mitla was occupied during Monte Albán’s zenith, it grew to its greatest size and importance later during the Postclassic period. At that time, Mitla was known as a place of ideological importance. The site is renowned for its elaborate cut-stone architecture, extensive palace complexes, and subterranean cruciform tombs. In fact, the name Mitla comes from the Nahuatl (Aztec) word Mictlan, derived from micca (corpse or tomb) and tlan (place). Its name in the local Zapotec language is Lyobaa, which translates as “entrance to the grave” or “place of tombs”—an appropriate title considering the number of burials that have been found at the site so far.

Fortress Excavations

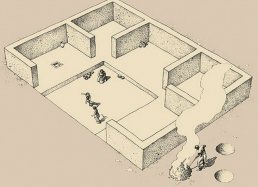

Many archaeologists have documented the Mitla Fortress, including Dr. Feinman and Linda Nicholas, who made an intensive map of the site in 1998. However, the current Field Museum studies are the first scientific excavations at the site. Several seasons of work have revealed that, like other sites, the hilltop residents not only buried their dead within their homes, but also tended to renovate and remodel these homes repeatedly, sometimes over many generations. Housing floorplans share similarities, too, consisting of a series of rooms arranged around a central patio where cooking, socializing, and craft activities took place.

Certain economic patterns at the Fortress have also come to light. For example, raising turkeys and knapping obsidian blades and other stone artifacts were common occupations—perhaps residents traded these goods with their nearby neighbors at El Palmillo, where rabbits and fiber items were more typical products. And as at other sites in this semiarid branch of the valley, ixtle (agave fiber) was a staple that was probably exchanged for corn with more distant Zapotec cities where wetter conditions prevailed.