2: Bad News & Good News from Mt. Pulag

I've just come down from our field site, on my way to the Wildlife Conservation Society of the Philippines conference in the central part of the country. The field work is going very well, with both a bit of bad news but some good news as well (more about that later). I'm a bit sore from the ride—on the back of a small motorcycle that reached its limit carrying the driver, my suitcase, and me—down the steepest, roughest mountain road I've seen in the Philippines, but otherwise, I'm extremely pleased with the work we've done so far.

The trip over from Chicago went well, and we were able to quickly check in with the Protected Areas and Wildlife Bureau and get their endorsement of this year's project. After purchasing supplies and packing gear, we then took a big bus up to Baguio, the "summer capital of the Philippines" that sits at the southern tip of the Central Cordillera, to coordinate with the regional office of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, and specifically with the Supervisor of Mt. Pulag National Park. That, too, went very well; they are excited to have us do our survey because they've had virtually no information on the mammals of the park.

So, after less than a week in the country, our team (Danny Balete, Joel Sarmiento, Nonito Antoque, and myself) arrived at the Mt. Babadak Ranger Station, the primary jumping-off point for entry to the park, at 8,000 feet in elevation. The road into the park is arguably the roughest, steepest road I've traveled in the Philippines; the mountain jeepney that we rode in was barely able to get past the worst spots.

Although we'd been forewarned, we still weren't prepared to see the extent of deforestation nearby the ranger station. Before the park was declared, there had been people of several traditional tribal groups living in the area, and they continue to see themselves as having the right to use the land. This wasn't a problem for a long time, since little could be grown in such a high, cool, wet environment. But beginning about 15 years ago in and around Manilla, the market for fresh vegetables—such as carrots, cabbage, potatoes, snow peas, and green beans—began to expand greatly.

With now more than 25 million people in Manila and nearby lowland cities, all willing to pay good prices for fresh vegetables, a huge market has been created. So, any place in the Cordillera that can be reached by road (even a bad road) is now being converted from mossy forest to vegetable farms. It's hard to blame the local people—they've been terribly poor, and the only other options for obtaining cash have been logging, mining, and other types of resource extraction that are just as bad as the farming, and maybe worse.

And so, within about a kilometer of the ranger station, I estimate that about half of the land is covered by neatly-tended vegetable fields, a quarter by brush or grassland with scattered pine trees, and only about a quarter by the original mossy forest. The forest is in patches, usually on the steeper slopes, with fragments ranging from only about half a hectare to 10-20 hectares. To make matters worse, about 20 years ago, heavy logging of large, mossy, forest trees pretty badly degraded the forest patches, with the original canopy made up of large trees now evident only in the big, rotten stumps scatted in the regenerating forest.

One of the first and most important questions that we must answer is, how well can the native, endemic species of mammals survive under these conditions? And how successful are the non-native pest species of rats at invading the forest remnants? And, for that matter, which species of rodents are living in the vegetable farms, damaging the crops that the local people work so hard to produce?

So we set about designing a strategy to sample all of the habitats in the area. We chose three forest fragments with varying levels of degradation from past logging (very high, high, and moderately high, since this is what's present), plus an area of grass and pines, and two small farms where the owners were more than happy to set traps to catch rats for us. Also, after a week, Danny began trapping in a good-sized patch of what seems to be virtually undisturbed mossy forest about 3/4 of a kilometer down and around the mountainside.

The results are surprisingly good news. Some of the most interesting of the endemic small mammals—species that have been poorly known and feared to be endangered—were present in all of the forest patches. These included two of the most distinctive species that feed almost exclusively on earthworms: the silver earth-mouse (Chrotomys silaceus—see Photo #1 below) and the tweezer-beaked rat (Rhynchomys soricoides—see Photo #2 below).

The most abundant species everywhere was a Cordillera endemic forest mouse, Apomys datae; we'd previously shown this to be a species that feeds on many types of food (although it also prefers worms). Other native species, such as the big Bullimus luzonicus (see Photo #3 below), which feeds on grass and herbaceous plants, and the pine forest mouse (Apomys abrae—see Photo #4 below) were uncommon, but at least present.

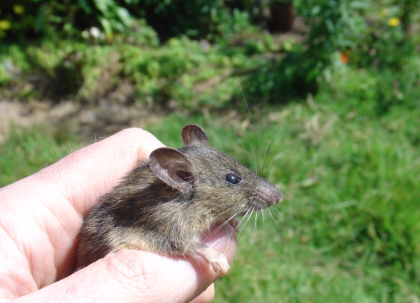

We were disappointed to capture only one arboreal species, Apomys musculus (see top photo above), a little mouse that is often common in both mature and disturbed mossy forest. The large tree-dwelling species of cloud rats, which are among the most distinctive and beautiful of Philippine small mammals, were seemingly entirely absent. Given the absence of the large canopy trees (where we think they usually live) this was not surprising—though quite disheartening.

Another bit of good news concerned the pest rats that are not native. Although these are invasive species in forests in some parts of the world, we found that Rattus norvegicus, the Norway rat, was confined to the farms and around buildings, never venturing more than about ten meters into the forest, and usually only at the forest edge or in the vegetable fields. The little rice-field rat, Rattus exulans, which is abundant and destructive in the lowlands, was likewise confined to the farms and other heavily disturbed habitat. Neither of these species had been able to penetrate the forest and displace the native species, even in heavily degraded mossy forest.

But the best news, though, came just three days ago, two days before the end of our survey at the ranger station and the move to the upper part of the mountain. We think we've found something very special, but we need to make sure, so stay tuned for breaking news in my next dispatch....

—Larry