6. Meteorite-spotting Practice Sessions

In preparation for our meteorite fieldwork, my colleagues and I spent some time practicing our spotting and collecting techniques. We looked for different locations where the movement of the Antarctic ice had delivered up rocks to its surface (see above photo.)

First, we walked the terminal moraines—rocks and sediments that form ridges marking the farthest advance of the glacier, in this case, where the inland ice encounters the Schirmacher Oasis. Next, we went to the spot where the inland ice meets the nunataks—isolated mountain peaks that project above the frozen landscape (see Photo #1 below.)

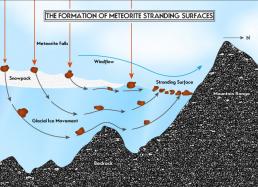

These locations provide a model of the glacial action that creates meteorite stranding surfaces. To explain, when an advancing glacier runs into obstacles (such as mountains), it “spins its wheels” in an attempt to climb over these big barriers. As this icy “conveyor belt” churns away, meteorites embedded within it get transported upwards, where they accumulate in spots called “stranding surfaces” (see illustration below.)

The ice along the nunataks and terminal moraines could, in theory, create potential stranding surfaces. However, this ice carries so much debris from the southward mountains that we’d be hard pressed to sort through all the terrestrial rocks to find the meteorites.

Nevertheless, these sites provided us with the perfect opportunity to familiarize ourselves with the types of rocks carried in the Anuchin glacier. We were specifically on the lookout for dark rocks that might be mistaken for meteorites at first glance, so that we could learn to easily distinguish the difference between the two (see Photo #3 below.)

Luckily, among the tens of thousands of rocks we examined, there were only two types of dark rocks, both of which were easily discernible from meteorites at close range. (Meteorites, while dark, often display a telltale, glassy “fusion crust” and smooth “thumbprints”—evidence of the their burning passage through Earth’s atmosphere. To learn more about meteorites, check out my Meteorite Basics Photo Gallery.)

From the southern edge of the Oasis, we were able to get a good view of the way in which many of the dark rocks littering the landscape arrived here—as part of the enormous debris load embedded in the ice wall. (Note the holes and dark bands visible in Photo #4 below.) The bands are fine sediments, and every dark patch is either a rock, or a hole where a rock used to sit before it fell out.

In the early afternoon when temperatures were highest, we could actually hear rocks periodically falling down from the wall as meltwater trickled from the glacier. It’s summer down here after all, and glacial meltwater is replenishing the lakes of the Schirmacher Oasis.

One of our collaborators has an ongoing microbiological research project at the Oasis and was supposed to come to Antarctica with us, but due to teaching obligations, he couldn’t make it. To help him out, we used our meteorite-spotting practice session as an opportunity to collect sediment samples from several of those lakes.

To our delight, while collecting samples we received a visit from some surprising company: a local Adelie Penguin (Pygoscelis adeliae), who seemed to be quite curious about what we were doing (see Photo #5 below.) He lost interest after a while when he realized we weren’t looking for something edible.

We also experienced close encounters with curious, low-flying South Polar Skuas (Catharcata maccormicki—see Photo #6 below), large birds that prey on Snow Petrels (Pagodroma nivea). Many of these birds have their nesting grounds on the Oasis and in the mountains near Untersee.

At this point, it was late in the day and the wind began picking up. Time to return to Maitri Station, where a delicious dinner with chicken curry, lentils, rice, chapatti, and a cup of hot tea awaited us!

More soon,

Philipp R. Heck, Ph.D.

The Robert A. Pritzker Assistant Curator of Meteoritics and Polar Studies

A Tawani International Expedition