4. Fieldwork at Untersee

When I last wrote, we had just set up camp along the Anuchin Glacier and were preparing to conduct a geophysical and geological survey of Lake Untersee. The glacier is unusual in that it flows southwards into the lake. Elsewhere in Antarctica, most of the ice flows northwards into the ocean surrounding the continent.

From our camp on the Anuchin, we had breathtaking views—an almost 270-degree panorama of the Gruber Mountains’ spectacular peaks and hanging glaciers, where we occasionally witnessed powder avalanches (see Photo #1 below.) Before us, ice stretched as far as the eye could see, towards the horizon and the continental ice sheet.

Our goal was to meet Dale Andersen and discuss upcoming plans with him and his team, who had set up camp along Untersee’s shoreline (see above photo.) Dale had already dived and sampled the lake this season, and he assured us that the lake ice was at least three meters (around ten feet) thick almost everywhere, thick enough by far for our heavy Pisten Bullies.

We headed down the glacier, deeper into the valley, and onto the lake ice towards Dale’s camp, again following a GPS route to avoid any wide crevasses on the glacier. Crevasses are the main reason one cannot simply drive around freely on the ice; following a pre-established safe route is a must.

We arrived at the campsite and were welcomed by Dale, his student Michael Becker, and his colleague Alfonso Davila. They invited us into their comfortable kitchen tent (see Photo #2 below) where, to their delight, we indulged in some high-calorie Indian delicacies brought along by my Indian colleagues. Over a cup of tea, we then discussed in depth the plans for our fieldwork at Untersee and our upcoming meteorite prospecting—my main motivation for the Antarctic trip.

The Indian Expedition had experienced some unexpected fuel shortages due to a delayed delivery, and we unfortunately couldn’t combine the Untersee work with prospecting higher up in the Gruber Mountains. The current plan is to perform the prospecting closer to Maitri Station in a trip later next week. Nevertheless, we were all excited to be at this spectacular location, where we could perform geophysical and geological work on the lake itself.

After our productive and amicable meeting with Dale’s team, Ashit and our driver, Hukam Singh, went for their first all-night Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey of the lake. The Pisten Bully towed the GPR antenna (see Photo #3 below), which recorded data continuously and provided a detailed map of the lake’s ice thickness—about 13 feet (four meters), much thicker than we expected!

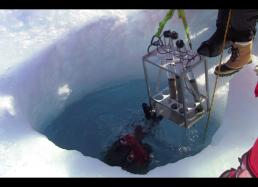

The next day, we witnessed Dale’s dive into the 36.5° F- (2.5° C-) cold water. I was glad to see him wearing a dry suit and full facemask (see Photo #4 below.) Dale is right when he says he feels warmer in the lake water than in the cold and windy air (14° F, -10° C)!

After Dale slid into the chilly water, we handed him the sediment sampling tubes, and down he went. A strong cord kept him connected to the surface. Through the intercom, he described his descent into the depths of the lake. Sunlight filtered through the dive hole and the thick ice, lighting up the surreal underwater landscape, where he encountered the large conical stromatolites that are, thus far, found only in this lake.

About 25 minutes later, air bubbles appeared again in the dive hole and Dale emerged with the sediment samples (see Photo #5.) Michael and Hukam pulled him out of the water and onto the ice. Being asked what the dive was like (see Photo #6 below), Dale said, “It’s like a trip back in time to the Archaean,” referring to the time about 3.5 billion years ago when conical stromatolites thrived.

With two more days available for work, Ashit and Hukam performed the second GPR survey, which involved filling in some gaps from the previous night’s survey and mapping the glacier tongue that dips into the lake. Raghuram and I hiked along the lake shore and moraines to collect some rock and soil samples.

During our nighttime hike, the sky was still a bright blue, but the sun was hidden behind the mountains and a strong wind made us feel really cold. I estimate that the wind chill must have been around -4° F (-20° C) (see Photo #7 below.)

Despite the cold, we were accompanied by curious Snow Petrels (Pagodroma nivea)—one of only three birds that breed exclusively in Antarctica (see Photo #8 below.) I also found several dead birds. The area is so dry that decomposition of organic matter is extremely slow, and I cannot tell if the birds died yesterday or years ago.

After about three hours in the chill, we returned to our vehicle, where Bishnoi, our driver, patiently waited to take us back to the camp for a good night’s sleep. Another day of GPR work and packing concluded our stay in the Gruber Mountains, and we headed back on an overnight to Maitri, where blessedly warm showers awaited us.

More soon,

Philipp R. Heck, Ph.D.

The Robert A. Pritzker Assistant Curator of Meteoritics and Polar Studies

A Tawani International Expedition